Kashmir handicrafts have commanded the admiration of the world for centuries because of their exquisite craftsmanship, captivating colors, and designs. The arts and crafts of Kashmir carry the image of the natural topography of the beautiful valley and the efficiency of its people to every nook and cranny of the globe. The Kashmir handicrafts particularly the carpet industry is economically very significant. Today, the carpet trade accounts for more than half of the total value of the valley’s handicraft exports. It is estimated that around 100,000 people are currently employed in the carpet industry, the vast majority of whom are from rural areas. The carpet industry employs the most children, and children make up a significant portion of the carpet weaving workforce.

Child labor trends in the carpet industry of J&K

According to an estimate based on the 1981 census, there are 1.5 million children working in the Kashmir carpet industry. According to Khatri, K. (1983), approximately 80,000 to one lakh children aged 6 to 14 were employed in Kashmir’s carpet weaving industry. Another study by Sudesh Nangia (UNICEF 1988) argued that 25% of the carpet weaving industry’s workforce is under the age of fifteen, and nearly a third of the total workforce is under the age of eight. A survey conducted by the Government of Jammu and Kashmir (1993) in 302 different areas of all the districts of Kashmir valley where the total number of child workers surveyed in surveyed areas is 11,281 revealed that 91.55% are engaged in various handicraft activities. Carpet weaving accounts for nearly 92.83% of the total child workforce in the handicraft sector.

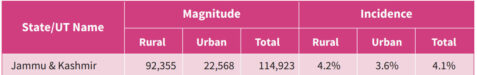

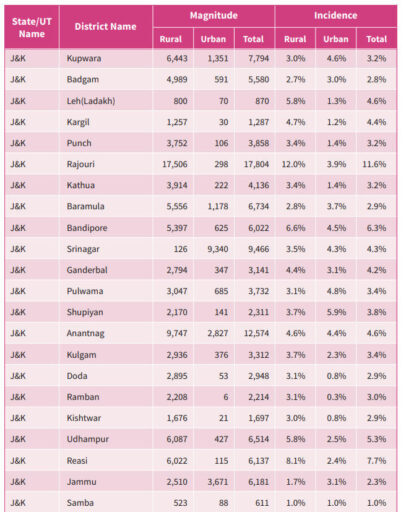

Census 2011 estimates that 10.1 million children (3.9% of the total child population) are working either as “main workers” or as “marginal workers”. The 2011 census counted 250103 child laborers in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The report titled ‘State of child workers in India: Mapping trends’ published in 2016 also presents a very grim situation. Table 1.1 underneath shows the magnitude and incidence of child workers in J&K whereas table 1.2 shows the district-wise magnitude and incidence of child workers.

Table 1.1 Magnitude and incidence of child workers in J&K

Source: Report titled State of Child workers in India: Mapping Trends

Table 1.2 Magnitude and incidence of child workers in J&K: Districts

Source: Report titled State of Child workers in India: Mapping Trends

A report titled “How Far is India from Complete Elimination of Child Labour as per Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8.7,” published by the New Delhi-based Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation in 2020 predicted that J&K will have 64.26 thousand projected child labor population in the 5-14 years age group by 2025. The foundation ranked J&K third in terms of child labor, which gives a good indication of the prevailing bleak situation. According to the report, UT is likely to maintain its third-place ranking in 2025 based on the projected number of children working as laborers.

Menace of child labor: Causes and consequences

It is confirmed from the above studies that the problem of child labor as a whole as well as in the carpet industry has assumed monstrous dimensions. Every stage of the carpet-making process involves children. At the raw material stage, they are associated with the production of thread balls. They are primarily employed in the weaving process, which is the most strenuous and time-consuming of all the operations involved in carpet production. Children are preferred because they are hardworking, easily available, easily disciplinable, and occupy less sitting space than an adult. Employers believe that children have flexible muscles and their nimble fingers help in the fine task of carpet weaving. Also, the carpet industry is labor-intensive, the entrepreneurs try to reduce labor costs and one of the ways to do this is to employ children on very meager wages. As per a research study, nearly 18% of children in urban areas and 14% in rural areas receive very low wages (₹1-4) per day. More than 70% of the children are being paid between five and twelve rupees per day. Another study conducted in 2012 reveals that the monthly earnings of child laborers in the carpet industry were ₹500.

Child labor in the carpet industry has assumed the significance of a “necessary evil”. According to a survey, almost all child weavers (96%) mentioned poverty as a major cause that drives them to seek some extra income. They believe that in absolute poverty conditions, child labor would at least guard families against starvation. Apart from being poor, many of the children have been forced into economic activity because they have lost one or both of their parents at a little age. Thus, the engagement of children in a way has evolved from an act of ‘exploitation’ to a ‘compulsion,’ with a working child now presuming the status of a serious bread-earner for the family.

The carpet industry is primarily a home-based industry. Carpet looms are established in homes. It becomes easy for families to engage their own children in addition to other children they may hire in carpet weaving. Thus, placing these looms in the premises of their homes and in their own communities facilitates the labor participation of children. The traditional system of employing children in family occupations has also been a contributing factor. A significant portion of parents wants their children to become proficient in weaving during their childhood so that they could buy their own looms and start independent work at home in the future. The low literacy among parents also affects the future of children. In rural areas with educational facilities, parents of poor, illiterate, and traditional families send their children to carpet-weaving centers, because to them, education seems to be of no use. Growing educated unemployment has also inculcated a notion among the majority of parents that there is no reinforcement after completion of education and as such, they are tempted to direct their children to various trades which yield them immediate results.

Employment of children in the carpet weaving industry has far-reaching socio-economic repercussions. Children in these factories work in small, dark, and crowded rooms away from sunshine and fresh air under poor lighting, ill ventilation, and unhygienic conditions. They are exposed to different types of pollutants like fibers, dust, dyes, etc. and as a result, the child workers are subjected to asthma and primary tuberculosis. The hunched-up position in which they work stunts their growth. The majority of children suffer from headaches, poor vision, backache, and abdominal pain. The worst affected is the education of the child. Very few children manage their studies and work simultaneously. Deprivation of education results in an irreparable loss not only for these children but also for their parents and for society as a whole. Karl Marx once said that “the result of buying the children and young persons of the underage by the capitalist results in physical deterioration and moral degradation.” His remark is evident in a field study which reveals that in around 80% of cases, the work life in the carpet industry results in moral degradation. Children pick up many unhealthy habits like smoking, gambling, snatching, pickpocketing, etc. The productivity of these victims in later life is lessened, the versatility and adaptability to different occupational conditions are curbed and their mental faculties are not properly developed.

Recommendations:

The prominence of this pernicious practice calls for urgent policy intervention. Education is the mother of all positive changes. Therefore, the education system must be made more accessible by rationalizing the admission procedures and improving the quality of teachers, books, curricula, recreational facilities, etc., to attract poor children. Child labor can be reduced if parents are compensated equal to their children’s earnings plus their educational costs. Poverty elimination programs such as NREP, IRDP, DPAP, TRYSEM, GRY, etc. should be effectively worked out in rural areas. Self-employment schemes should be intensified. While drafting policies, prioritizing areas with a high concentration of child laborers is the need of the hour. In addition to poverty elimination programs, the minimum wage should be raised so that children can continue their schooling.

Periodic community sensitization programs on the negative consequences of child labor, including the impact on the health and future of the children, the family’s economic situation, and the negative impact on the community and society at large, should be conducted. Vigorous enforcement of existing child labor legislation supplemented with practical social measures such as organizing facilities for education, health, nutrition, and skill development among working children, and finally monitoring the progress of program implementation would go a long way toward combating child labor in the valley. Civil society partners must be trained to assist in identifying and monitoring units where child labor is used, as well as to assist the law enforcement machinery by appearing as independent witnesses in cases filed under child labor laws, thereby playing a pivotal role in achieving convictions of offenders.

Conclusion

The magnitude of the problem of child labor in the carpet industry is severe. From the foregone study, it can be deduced that child labor is a complex problem that stems from low socio-economic status. Furthermore, the traditional mindset and accelerating educated unemployment in the region also contribute to the persistence of child labor. The working conditions of these tiny hearts in terms of hygiene are horrible. They are exploited in the most dehumanizing way. It is a multifaceted problem that eventually impairs the personality and creativity of future generations. Given the complexity of the problem, a multifarious, multidimensional, involving multiple stakeholders and social partners, with a coordinated and inter-sectoral approach is required. J&K must act fast to prevent child labor from becoming a lasting hurdle in the achievement of SDG 8.7.

References:

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/27767541?read-now=1&seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents

- https://www.dailyexcelsior.com/child-labour-continues-to-be-a-concern-in-jk/

- https://vvgnli.gov.in/sites/default/files/State%20of%20Child%20Workers%20in%20India-Mapping%20Trends.pdf

- https://kashmirlife.net/kashmirs-carpet-industry-1454/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329809502_Carpet_Handicraft_Industry_in_Kashmir_an_overview

- https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JLPG/article/viewFile/1884/1839

- https://www.academia.edu/32960564/An_Empirical_Analysis_of_the_Child_Labor_in_the_Carpet_Industry_of_Kashmir_Some_Major_Findings

- https://groundreport.in/child-labour-kashmir/

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.