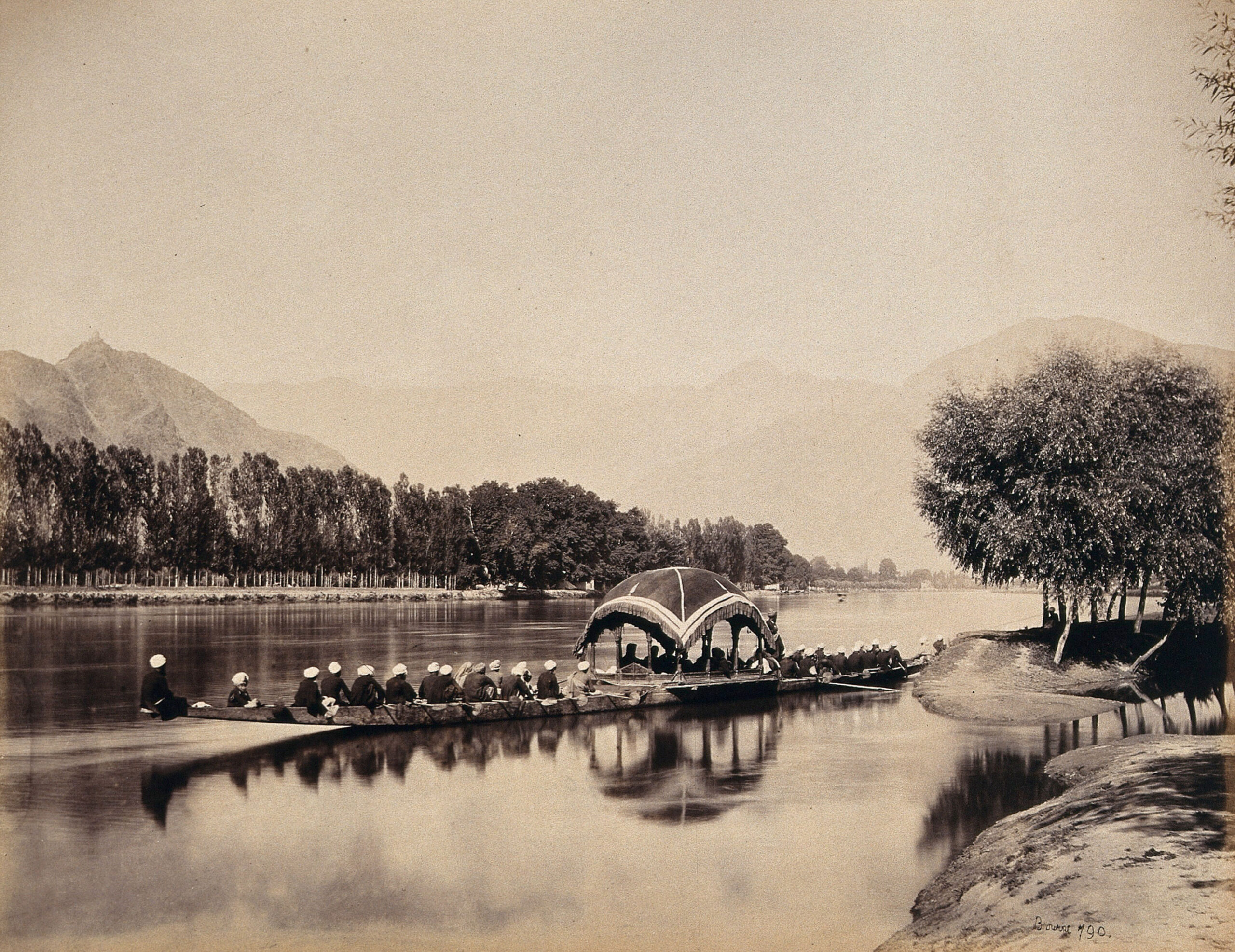

In 1949, Jawaharlal Nehru visited the United States and received the kind of reception that suits a national hero. However, his welcome in the United States paled in comparison to what he received two weeks ago in Srinagar, regardless of how loud the sirens of the motorcyclists sounded. The two-and-a-half-hour ride on a boat along with Sheikh Abdullah on the Jhelum was the ultimate reception befitting a country’s leader. Nehru glided on its muddy stream in triumph. It was pulled by white-uniformed rowers wearing red turbans. On a podium resembling a throne where Nehru sat. A trip on a waterway is the perfect way to get a taste of any place, and Nehru experienced the ultimate one on the Jhelum. The reception depicts the importance of the Jhelum waterway in Kashmir’s culture.

In the past, Kashmir, particularly Srinagar city, was the centre of inland water routes, and these were always used to give aesthetic pleasure and an artistic view of nature and culture to tourists. These routes connected it to different parts of the city, which earned it the title ‘Venice of the East’. Inland water transport has been a jugular vein and a vital tourist attraction since ancient times in Kashmir. In the last decade of the 15th century, Jahangir, along with his favourite wife Noor Jehan, travelled the Jhelum in a flotilla of royal dungas, immersing themselves in the romance of the ride, compelling Jahangir to visit Kashmir frequently.

Similarly, in the 17th century, Aurangzeb and Bernier travelled the same inland water route, and Baron Charles Hügel, the irascible German, did the same in 1840. With advancements in road traffic, inland water transport went out of sight, and no one cared for it. Thus, huge potential for waterways remains unutilized, and these routes shrink and few vanish as no one looks after them.

As time passes, making the Jhelum navigable today becomes a little complicated but not impossible. Pertinently, the central government has taken numerous initiatives to unlock the potential of waterways through Sangarmala and other projects in India. Through these initiatives, four major rivers of J&K, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, and Indus, were identified as national waterways, outlining the vast potential for inland water transport. The Jammu and Kashmir government should also realize its potential and future benefits through timely investment in this sector so it will adorn the beauty of UT, particularly Srinagar city, and will also be a source of traffic and revenue.

Initiatives taken to restore and develop Inland Water Transport in J&K

Jammu and Kashmir is endowed with a variety of navigable waterways comprising river systems and some famed lakes. However, the navigable waterways remain confined to limited locations with traditional technology. Inland Water Transport (IWT) is functionally important in Kashmir, which is bisected by the river Jhelum and its city is crowned with vast Dal and Nigeen Lakes. Similarly, in north Kashmir, lies the Wular and Manasbal lakes where IWT offers natural advantages. IWT is crucial for J&K since it provides a cost-effective, energy-efficient, highly employable, and nearly pollution-free form of transportation. Despite the benefits of IWT, a number of known and unknown issues limit its use, and the government did not pay heed to developing navigation water transport in the valley.

Pertinently, in 2018, four major rivers, including the Jhelum, Chenab, Indus, and Ravi in Jammu and Kashmir, were declared “national waterways” by the Union government, with a motive to boost water transport and tourism in Kashmir. A delegation from the Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) held a meeting with the government of J&K in 2018 to discuss the inland water transport capabilities of J&K. Pertinently, IWAI has carried out hydrographic surveys and formulated a feasibility report for a portion of the River Jhelum with a length of 110 km, i.e., from Sangam to Banyari (Wullar Entry).

The J&K Government has also identified its extended scope for navigation routes in Wullar Lake, from Sopore to Baramulla, from Sumbal to Manasbal Lake, and from Shadipora to Duderhama (Qamar Sahib Shrine). However, due to political instability, no concrete steps were taken. Five years have passed, and the fate of inland water transport service remains uncertain. In 2021, bus boats were brought from New Zealand, and they were supposed to ply from Lasjan to Downtown Srinagar. However, due to some reason, they could not sustain long. Recently, the Municipality Commission Srinagar vowed to start water transport in 2024 in the city. However, the governor’s administration should think beyond Srinagar city and formulate strategies and planning to make the Jhelum navigable from Anantnag to Baramulla along with other rivers. It will help in agriculture, horticulture, and other products transportation along the river.

Historically, the Jhelum River has served as the backbone of Kashmir’s transport system. The remains of Ghats along the banks of the Jhelum in Srinagar indicate the city formerly had an inland water transportation network. The city’s water transportation system needs to be revitalized to support its road-based transportation network. Simultaneously, it will serve as a major draw for tourists to experience the beauty and historical significance of this city. With an estimated length of 165 KM in India up to the existing ceasefire line, the Jhelum can form the backbone of water connectivity in Kashmir. It can be to Kashmir what the Grand Canal is to Venice. The width of the Jhelum is around 300 m, but in Srinagar city, it is reduced to 200 m, indicating that it still has vast potential for water transport. Like the Grand Canal of Venice, the Jhelum waterway, with minimal capital investment, will become such a desirable destination that it will offer stunning views of agriculture fields, Chinars, beautiful mountains, and city architecture. Thus, it can attract more tourists to the valley.

As research suggests, in Srinagar city, taking advantage of these natural water transport routes, from Raj Bagh to Chhatabal (along the Jhelum River), Dalgate to Hazratbal/NIT 3, Dalgate to Soura via Nallah Amir Khan and Khushalsar, Dalgate to Hazratbal via Nishat, Shalimar, and Pampore to Raj Bagh, can be developed with minimum capital investment in initiation. It doesn’t require huge capital investment in construction except for prior research, planning, and assessment. Similarly, in other districts, such vital routes can be utilized for transport and tourism, from Shadipora to Duderhama (Qamar Sahib Shrine), from Sumbal to Mansbal Lake, and from Sopore to Baramulla, and on the outer lakes and tributaries. Introducing a variety of water transport options, including ferries, canal buses, boat cruises, water taxis, canal bikes, and boat rentals, could enhance the charm of the area while simultaneously stimulating the economy and alleviating strain on surface transportation.

Recommendations

It is difficult to keep the Jhelum navigable all year round. As it stands, the river can only be navigated during the summer months when the water is high, which restricts the effectiveness of the transport system to certain areas. A system of weirs or barriers across the river would be necessary to achieve year-round navigability, raising water levels during low seasons. However, these installations may present issues during flooding. Controlled opening might be possible during the rainy season with a contemporary approach that incorporates technology. Currently, the single weir at Chattabal, constructed in 1905 by the Dogra king Hari Singh, elevates the Jhelum’s level from Chattabal to Pampore.

The absence of a dedicated government authority to administer the various aspects of the Jhelum poses challenges, with water, bunds, and bridges falling under separate departments. A suggested solution is the establishment of a new department solely focused on managing inland water transportation. Examples from Bengal, Kerala, and other states of the country that have dedicated separate departments for running water transport can be taken into consideration.

In the late 1990s, proposals surfaced to launch an inland water transport system to ease road congestion. A trial occurred in 2012, leading to a pilot project. State-run motorboats operated until 2014 when floods damaged them. Today, only a few wooden boats remain, owned by locals, ferrying passengers near Lal Chowk. In 2016, 2018, and so on, the government aimed to revive water transport for cargo and passengers, but they remained unsuccessful. Experts suggested that these projects failed as the administration did not bother to conduct pre-feasibility assessments to evaluate the long-term viability and repercussions of the policies. Thus, there is a need for pre-assessment and research so that such projects can run successfully in the long term.

Conclusion

The inland water routes are in the perfect position in the valley, adding glamour to Kashmir. The journey from Anantnag to Baramulla through Srinagar city can be the ultimate trip for tourists. Transportation on these waterways can beautify the valley further, along with providing other economic and environmental benefits. This water route will also enable the transportation of agriculture and horticulture products from orchards and fields lying along the river. It is the target of the central government to modernize and develop the inland water transport system throughout the country. The UT administration should also initiate long-term projects on these water bodies. Inland Water Transport (IWT) will play a larger role in attracting tourists and alleviating pressure on roads, and particularly, it can play a crucial role in adorning Srinagar city. With proper planning and minimal funding, these inland waterways can provide employment and generate significant revenue in the future. Take, for example, the Gulmarg Gondola, installed in 1993 for 30 crores, now earning revenue of 600 crores annually. Similarly, timely investment in this sector can prove to be an important feature in the tourism and transport of Kashmir.

References

https://kashmirvision.in/2018/01/31/4-major-rivers-in-jk-declared-national-waterways-jk-govt/

https://www.wionews.com/india-news/revival-of-water-transport-in-kashmir-bus-boats-bought-from-new-zealand-398308

https://www.jkhudd.gov.in/pdfs/Master-Plan-2035-ReportFinal.pdf

https://scroll.in/article/845565/gently-down-the-jhelum-is-water-transport-in-kashmir-a-practical-option

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.