Looking back over the past 30 years, the people of J&K have witnessed enough instances of coordination breakdowns among institutions/functionaries.

If peace and stability in Jammu and Kashmir are at the heart of the government agenda then there is no reason why its institutions/functionaries should not work together. With that being said, lack of coordination between them gives rise to poor and inefficient planning and thereby results in wastage of time, money, and efforts. Above all, a blunder committed by one agency/functionary undercuts the efforts of the other agency/functionary.

Looking back over the past 30 years, the people of J&K have witnessed enough instances of coordination breakdowns among institutions/functionaries. For starters, let’s take the example of twenty-one-day long ‘Janbaghidari Abhiyaan’ launched by the UT administration.

The government of Jammu and Kashmir is currently holding a public-outreach programme –‘Janbaghidari Abhiyaan’ (public participation) — in the form of developmental interactions, as a run-up to what is going to be the third phase of its ‘Back to Village’ (B2V) programme beginning on October 02, 2020. Without going into too much detail of the third phase of B2V, and taking it on face value, it goes without saying that reaching out to the people to assess their developmental needs and gauge their aspirations and moods vis-à-vis basic issues of governance is a great step, and could yield positive results if backed up with serious and sincere political and administrative will.

More to the point: If “war is development in reverse”, then there is certainly a case for development also impacting the health, longevity, and outcome of wars. The World Bank says that “war retards development” — that “where development fails, countries are at risk of becoming caught in a conflict trap in which war wrecks the economy and increases the risk of further war.”

Having said that, Kashmir has been witnessing year-on-year growth in this “war retards development” phenomenon. If, for the sake of argument, one were to discount the political reasons of the conflict, lack of development or failure of developmental promises to translate into reality on the ground, emerge as the primary reason driving the conflict here. However, “where development succeeds, countries become progressively safer from violent conflict, making subsequent development easier.” (‘Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil War and Development Policy’ – A World Bank Policy Research Report, 2003).

So there is a reason for the government to pursue development for neutralizing the sting, impact, and prevalence of the armed conflict in Jammu and Kashmir, and ending the scourge of conflict for the larger good of building sustainable peace, and also to bring about further development with greater ease. Seen this way, there is no reason why civilian and security initiatives shouldn’t go hand in hand, supplementing and complementing each other for long-lasting peace in Kashmir.

The need for closer relationship and coordination among the civil administration and the security agencies is felt both at a conceptual and as well as on the ground level. So, when there is a need for military measures to deal with and contain the violence (and its potential use), there is, at the same time, also a desperate need to addresses broader questions like what pushes and persuades people towards separatism. And this cannot be done by employing security measures alone. The government has to employ an all-round approach to get it done — the end of a one-size-fits-all approach. According to David Cortright, “prioritizing military approaches diverts attention from the difficult challenge of addressing the underlying economic, political, and social conditions that contribute to state weakness and increase the risk of armed conflict.” This is where developmental comes in. By reaching out to the common masses with possible deliverables and not mere promises of development, the government has a chance to employ this all-round approach in Jammu and Kashmir.

Development can, in military parlance, thus be described as a “non-lethal” weapon of war. And once employed with sincerity of purpose, it could well change and impact the contours of war in unprecedented ways — something which even the lethal military machinery cannot, and has not been able to achieve, either in Iraq or Afghanistan or elsewhere. Kashmir is certainly is no exception to that.

However, the unfortunate episodes like the one that took place in Shopian on July 18, 2020 — where three innocent labourers from Rajouri district were killed and then labeled as “terrorists” by the Army — or the Sopore incident of September 15, 2020, when a youth picked up by the police was found dead under mysterious circumstances prove that civilian and military structures are working at cross-purposes, not only undermining but even negating the possible benefits of most notable government initiatives.

This has to end. Let these two unfortunate incidents put a ‘full-stop’ on such blood-letting. And it won’t happen — as it hasn’t thus far – unless and until the responsibility is fixed and the guilty are punished as per law. Doing justice to the victims and their grieving families is of course important, but equally important is also that the general public needs to see justice being done. Let an ordinary Kashmiri be reassured that she/he is not after-all expendable; that her/his life and dignity matters!

Inspector-General of Police Kashmir range Vijay Kumar on Friday said that results of DNA samples of parents of three youth from Rajouri district have matched with those killed in Amshipora, Shopian on July 18 this year and police will now take further course of action. It is expected that “further course of action” is not delayed and the youths killed in the encounter will get justice soon.

Reducing the scourge of ‘new wars’ (intrastate internanationalised conflicts), Mary Kaldor writes {‘New and Old Wars: Organised Violence in a Global Era’ (3rd edition)}, will require overcoming the politics of exclusion and restoring the legitimacy of public authority and the rule of law.

Here is yet another golden opportunity for the governments – in Srinagar and New Delhi – to make an assertion – loud and clear – that extra-judicial executions or “fake encounters” are unacceptable. That the security forces conform to their obligation under the law while dealing with the situation in Kashmir, and any contravention of the set protocols won’t be tolerated.

In Kashmir, organized combat between the militants and the security forces (including army, police, and paramilitaries) is a routine, and so are assassinations and armed criminality. The violations of human rights too are frequent. There’s no denying that combatants use violence to terrorize opponents. It is not unusual for the non-state actors to exhibit criminal behavior, who are not bound by any rules or laws, nor are they answerable to any chain of command; however, such behavior cannot be condoned if manifested by the security forces.

When on the battleground, the operational commanders or the soldiers may, in the heat of the moment, feel that there are no distinctions between the private and the public, non-state and state, formal and informal, internal and external, and what is done for political reasons or economic purposes, but those placed higher up in the military and political hierarchy cannot afford to remain oblivious to these distinctions. The goal, on the ground, as Kaldor writes, is less winning “hearts and minds” and more the sowing of “fear and hatred”. But this cannot, and certainly is not the goal at the political helm. If the goal of the government is to win “hearts and minds” of the people, it cannot be achieved by “having them by the balls”.

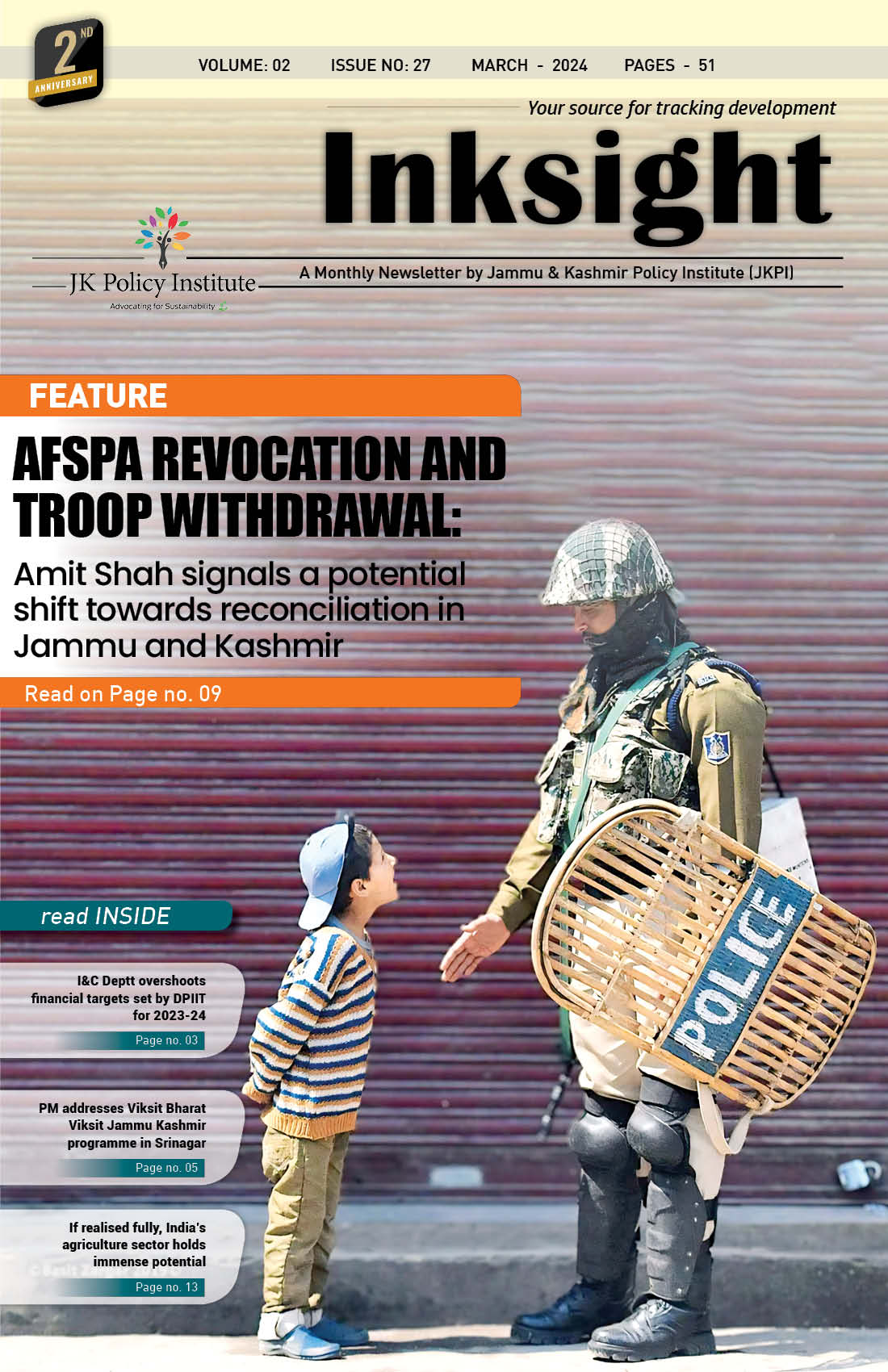

In a place like Kashmir, people come face to face with, on a daily basis, police and military more than they get to see officials of civil administration – the situation is widespread in rural areas that witness a larger presence of security forces and less visibility of civilian administration.

Charles T. Call and Willaim Stanley say, “The tenor of these interactions, particularly the fairness of police (read security forces including the army) conduct with respect to both individual and group rights and the police’s (again read security forces’) moderation in the use of the force will have a significant effect on whether the public trusts and supports the new order” – i.e. the government.

Police scholar David Bayley says, “The police (again it must also include the army and other institutions performing policy-making jobs in Kashmir) are to the government as the edge is to the knife.”

Abusive, corrupt or neglectful conduct of military structures can quickly undercut public commitment to the government, and public order, and can lead to a variety of damaging reactions such as reconstitution of ethnically or ideologically driven exclusivity, biases, prejudices, and stereotypes, which then go on to create more strife and hatred and violence.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s).

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.