Pheran had this unique quality that as long as it was on me; it could conceal both the pitiable condition of my clothes and the not-so-good economic condition of my family, and maybe many more similar other vulnerabilities as well.

Given a choice, and a chance, as I had as a kid – to run away from the tailor’s shop – they too would do anything and everything so as not to take off their Pheran. But unfortunately, the situation, for most of them, is such that it is not a tailor requesting them to take off Pheran or a kind father prodding them to do it.

I might have been ten or twelve years old when my father took me to a tailor in our village. During those days, we would get a pair or two of the shirt and pyjama pants stitched every winter – which was made of wool-like synthetic fabric “Kashmilon” (as it used to be called). For stitching this winter dress, the tailor had to take my measurements. He asked me to take off my ‘Pheran’ (long woollen overgarment worn in Kashmir during winters) so that he could do the job. But I wouldn’t do it, the reason being that beneath that long overgarment whatever clothes I was wearing were worn out, burnt and shredded due to persistent use of Kangri (a traditional clay firepot weaved into willow wicker, which keeps people in Kashmir warm during harsh cold winter months) that I felt ashamed to take off my Pheran. It occurred to me that I should not let anyone see the poor condition of my clothes. Like any human being, I felt shame at myself for wearing tatty clothes. So, when the tailor and my father insisted that I should take off my Pheran, I jumped out of the shop and ran away.

Nonetheless, the poor tailor somehow managed to sew the winter dress without taking my measurements – and let me tell you that it did fit perfectly well! But this episode, even today, I so vividly remember, had, perhaps for the first time, made me feel so vulnerable. Exposing the pitiable condition of my clothes would, in a way, be a reflection of my being a careless brat who wouldn’t take precautions while using a Kangri. But on a deeper plane, it would also be an indictment of the not-so-good economic condition of my family.

Pheran had this unique quality that as long as it was on me; it could conceal both the pitiable condition of my clothes and the not-so-good economic condition of my family, and maybe many more similar other vulnerabilities as well. So how could I have taken my Pheran off just because a tailor had asked for, or my dad had insisted? Come on, it was not an easy decision. How could I have agreed to a revelation of such a magnitude?

That was then – maybe some twenty-odd-years back. Times have changed since then. Today’s kids, I suppose, may not face the kind of fears and dilemmas our generation has braved – or maybe they do too. I don’t really know. But one thing is for certain that even today people may have their own weaknesses that they may want to conceal under their Pheran.

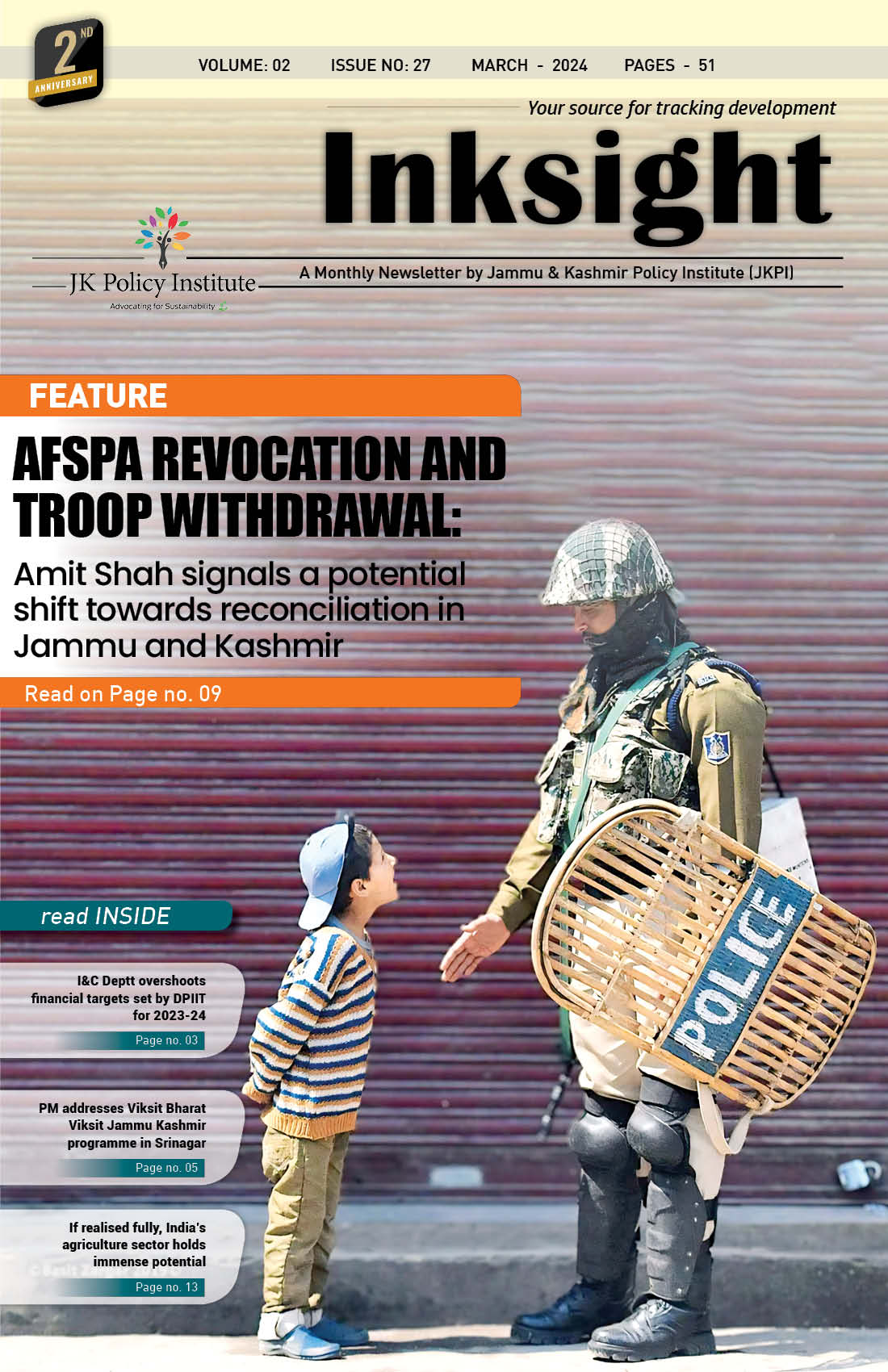

Given a choice, and a chance, as I had as a kid – to run away from the tailor’s shop – they too would do anything and everything so as not to take off their Pheran. But unfortunately, the situation, for most of them, is such that it is not a tailor requesting them to take off Pheran or a kind father prodding them to do it. All of a sudden, in a busy marketplace, a road or a street, in the full public gaze, they are commandeered into a line by a posse of gun-toting cops and ordered to take off their Pherans and jackets and raise their hands up so that they could be searched and scanned to preempt any potential trouble they may be up to.

The men in the uniform may think that this frisking is the best way of identifying and catching the trouble-makers, but it needs to be understood that not everybody is a trouble-maker, carrying a gun under the Pheran. When they look at everybody as a potential “terrorist”, they are humiliating and thus turning away a huge chunk of common, ordinary people whose singular claim to the state and its systems is that they be treated with respect and dignity.

By state’s own admissions, and the common sense, as well as, the facts on the ground also testify it — those who cause trouble are only a minuscule minority, while a vast majority is of those who want to go about their mundane life without bothering themselves, or anybody else. But when everybody is painted with the same brush, treated with absolute scorn and disdain and forced to take off their Pherans — the move is bound to be counterproductive. It’s debasing and dehumanizing as much as it is humiliating to be at the receiving end of such a treatment.

In the early days of trouble in Kashmir, when militancy was at its peak and the security forces were just getting the ‘hands-on-job training’ on the measures to contain it, perhaps it was OK to go for such “crackdowns” (as the exercise would be called) wherein entire populations would be paraded before the masked informers (‘Mukhbir’) placed inside the police jeeps. But 30 long years is, without any doubt, too long a period for any training. By now policing of the militancy should have reached a certain degree of maturity and sophisticated smartness for any preemptive and punitive action to be pointedly accurate, smart and target specific, and certainly not indiscriminate, disoriented or disjointed.

Moreover, we are living in changing times. Thanks to social media, it takes just one click of a camera to name, blame and indict. Even a routine photograph, if clicked from an appropriate angle and then posted on social media with a proper mix of words to ring out the horrors of such demeaning exercises has the potential of creating massive public outrage – even beyond the sovereign boundaries of a state.

In the wake of two back-to-back militancy related incidents in Srinagar past week – when a civilian -Krishna Dhaba owner’s son was shot at in high-security Durganag area, and later two unarmed policemen were gunned down in Baghat area along the high-security Airport road – we didn’t see the kind of public outrage such incidents should have generated. It’s unfortunate. But it is also true that if the common people choose not to call out on militants for their dastardly and despicable acts, they do it on purpose. They know what such defiance would entail.

Blunt and crude it may sound, but let’s face it — if the police have not been able to secure and shield their own personnel from the sneak attacks of the militants, why should ordinary people nurse any belief that the same police will thwart and ward off any reprisals coming their way should they choose to openly oppose the militants and their actions?

The overall security situation here is yet to enthuse the popular encouragement needed for such confidence. This is a fact that must be admitted. So should be that people’s silence is not their support or endorsement of whatever the militants do. They cannot condone their actions, particularly when the civilians or the non-combatants are at the receiving end of sadistic and psychopathic lunacy.

It is, therefore, important that ordinary people are not blamed for something they have not done or condoned. Instead of relying on old ramshackle and indiscriminate security measures which end up annoying ordinary people, it’s time for the men in Khaki to evolve with smart operations, with minimal physical and psychological “collateral” damage.

Common-sense policing together with efficiently calibrated human and technical intelligence makes it possible to specifically pinpoint the ones who carry guns inside their Pherans. Master this art and you will not have to undermine the ordinary people’s sensitivities and expose their vulnerabilities by asking them to take off Pheran.

Remember the story told about my childhood. Most people hide their vulnerability beneath their Pheran, which they don’t want to show. They may even risk forgoing a brand new dress for it. Respect their sensibilities, please.

The views and opinions expressed in this Blog Post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of JKPI

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.