It is important to explore or describe a community or group statistically. Numbers matter because it brings to light the significant aspects of that group, their problems, demands, and aspirations. Numbers help us to question the binaries of accessibility and inaccessibility, representation, and redistribution of resources among its heterogeneous population. The lack of accessibility leads to the marginalization of a few communities from the larger picture of inclusive developmental activities, furthering the wedges of socio-economic disparities in the realms of education, poverty, employment, and health among them. It is very important for the state to put in welfare measures for the least advantaged sections of society for inclusive and sustainable development.

When it comes to the availability and accessibility of healthcare facilities for socially or culturally marginalized communities in the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), Gujjars and Bakarwals remain on the margins of the healthcare system.

J&K has a heterogeneous demography, with people belonging to different ethnic groups with regional and spatial variations. According to data from the 2011 census, Jammu and Kashmir had a population of 1,25,41,302, with 66,40,662 men and 59,00,640 women. 14,93,299 people belonged to a scheduled tribe, which represented 11.9% of the state’s total population. The Gujjar population of the former state was estimated to be 9.8 lakh, while the Bakarwal population was 2.25 lakh.

The Gujjar and Bakarwal communities are indigenous people who have traditionally lived as nomadic pastoralists in the northern regions of India, including Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttarakhand. These communities have a unique way of life that revolves around their livestock and the natural resources they depend on for their livelihoods. However, despite their rich cultural heritage, these communities face numerous challenges, including poverty, lack of access to education, and discrimination. These challenges have also contributed to the poor health status of these communities, with high infant mortality rates, malnutrition, and lack of access to healthcare facilities being major issues. The undernutrition, vitamin deficiencies, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and thyroid problems that plague the tribal tribes in Jammu and Kashmir are severe, and they are compounded by the fact that they have little access to healthcare.

According to the National Family Health Survey, the infant mortality rate among the Gujjar community is 46 deaths per 1,000 live births, while among the Bakarwal community, it is 60 deaths per 1,000 live births. Malnutrition is also a significant concern, with many children in these communities being underweight or stunted.

Prevalence of vitamin deficiency

Vitamin deficiency (VD) is highly prevalent among Kashmiri tribals with 66% having Vitamin D deficiency (VDD),14.71% having insufficient and only 19.3% having sufficient serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D written as 25(OH)D levels despite their good sun exposure. This leads to stunting of children due to rickets and poor bone mass in adults.

Prevalence of hypertension

The studies reveal that the prevalence of hypertension is increasing among all ethnic groups across the globe. For instance, Ganaie conducted a cross-sectional survey that included 6808 tribal aged 20 years (5695 Gujjars and 1113 Bakarwals) from five randomly selected districts of Kashmir. The study finds that the participants belonging to different age groups were examined and the prevalence of hypertension overall was 41.4% (39.9-42.9%) (95% confidence interval (CI)). It also found that the prevalence of prehypertension (95% CI) was 35% (33.7-36.6%) in women and 46.7% (44.1-49.1%) in males. Significant risk factors for hypertension included older age, passive smoking, family history, and obesity.

Prevalence of diabetes

Although diabetes prevalence has been reported to be less (1.26 %), which is somewhat like that of Europeans, the magnitude of prediabetes was very high (15%) despite the low magnitude of obesity (8%). Thyroid and Iodine deficiency disorders are quite rampant in people living in the upper reaches of mountains and Gujjars due to the non-availability of iodine in their food intake. Tribal peoples are still the most malnourished group in Indian culture today. According to the most recent data, 4.7 million Indian tribal children experience chronic malnutrition, which has an impact on their survival, development, learning, academic achievement, and adult productivity.

A study assessing the nutritional status and health issues of Gujjar women of Bandipora district of Kashmir showed that Gujjar women of Bandipora district are undernourished. Poor diet intake, ignorance, early marriage, and increased morbidity due to unsanitary practices and surroundings are a few possible causes of undernutrition in tribal women. The poor health status of the Gujjar and Bakarwal communities can be attributed to several factors. Poverty is one of the main reasons for poor health, as it limits access to food, clean water, and healthcare. Another study that assessed the socio-economic and demographic profile among the tribal population of Kashmir and their major risk factors for some non-communicable diseases said that around 94.3% of the tribal population fell under low-income groups with an annual income of Rs. 25000 per year. Only 37.1% of subjects were educated. For 61.0% of tribal subjects, access to clean drinking water and adequate sanitation is a problem. It’s interesting to note that 63–66% of the population was younger, and smoking was highly prevalent among both men and women (33.3% of men and 7.3% of women, respectively).

Many Gujjar and Bakarwal families live in remote areas and lack access to healthcare facilities, which contributes to the high infant mortality rate. Additionally, traditional cultural beliefs often prevent people from seeking medical care, leading to delays in seeking treatment or avoiding it altogether. When it comes to achieving the necessary income, education, health, and other conditions for excellent community nutrition, tribal communities, particularly women, lag behind other communities. Due to their lack of education, Gujjar women frequently live unhealthily complicated lives. The worst treatment of Gujjar women was also brought to light by Gul (2014), who demonstrated how their physical and mental frailty was caused by a life of hardship and toil. These women were also discovered to be at greater risk for pregnancy and childbirth.

The inability of these groups to learn about adequate nutrition and hygiene is another factor that contributes to poor health. The scheduled Tribe has a literacy rate of 50.6%, which is significantly lower than the national average. It should be mentioned that the literacy rates among Gujjars and Bakarwals are appallingly low. According to data from the 2011 census, the literacy rates for men and women are respectively 60.6% and 39.7%.

Access to maternity care

Gujjar and Bakarwal women face unimaginable difficulties when it comes to healthcare services, owing to their remote geographic location and uneven terrain. It is a nightmare for impregnated ladies as the lack of road connectivity, transportation, communication, and uneven weather adds more misery to their already critical condition.

The pregnant ladies have to travel long distances before reaching the tertiary health care centers in Srinagar. Some deliver even before they can reach the health centers. On many occasions, they die on the way to the healthcare centers because it takes a considerable amount of time to reach the hospital. Lack of pedestal paths, and if any that again is sometimes not even fit to walk in uneven weather be it during rain, wind, or snow. Coming down from hills and mountains, and traversing these difficult terrain to avail transportation facilities is extremely difficult and fraught with risks. These indigenous communities complain that they are unable to avail of any services from PHCs near their areas also.

Ground realities and potentialities

The reach of government and non-governmental organizations in implementing various programs for the healthcare and nutrition facilities of the Gujjars and Bakarwals communities is an ongoing process. While the Government has set up various mobile health clinics to tackle the accessibility conundrum, Non-governmental organizations have been steadfast in performing their duties to provide adequate healthcare facilities and ensure optimal nutritional intake by setting up nutrition centers. Furthermore, unfaltering attention to the educational needs of the Gujjars and Bakarwal is being devoted. Many organizations have rooted for ameliorating their educational status which yields cross-sectoral dividends such as greater awareness regarding health, hygiene and nutrition, employment opportunities, and creating a class of civilized citizens, etc.

Despite sustained efforts to recuperate the decaying healthcare levels among the Gujjars and Bakarwals, an array of reports and research documents present a dreary reality. For instance, research titled “Traversing the margins: Access to healthcare by Bakarwals in remote and conflict-prone Himalayan regions of Jammu and Kashmir” found that just 51% of primary health care (PHC) facilities possessed the required physical infrastructure and services and owing to the scarcity of healthcare services, the lives of these communities remain on the periphery of inclusive development. Apart from the institutional and infrastructure deficiencies, one of the most significant barriers to upgrading healthcare levels is the geographical location and isolation of Gujjars and Bakarwals.

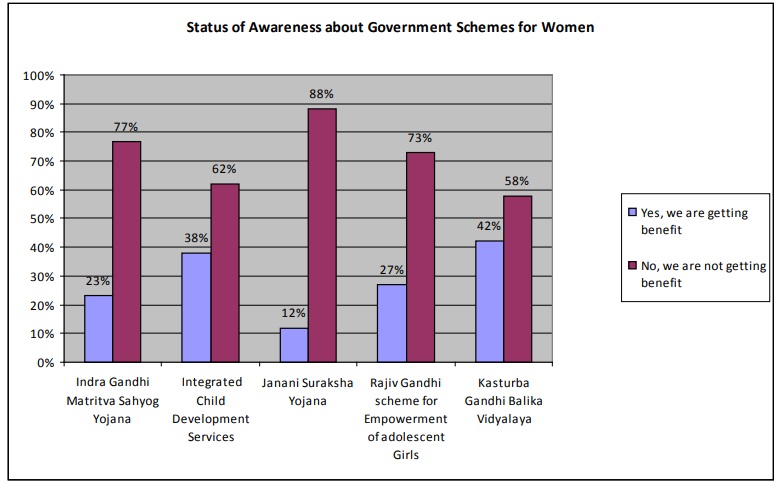

Within the community fold, the most deplorable lot is that of the women. They are the worst affected when it comes to taking advantage of government programmes for better health and nutrition. There are no reservations about the fact that the Central, as well as State Governments, have launched a number of programmes and schemes for the betterment of rural as well as urban women like Indira Gandhi MatritvaSahyog Yojana, Integrated Child Development Services, Janani Suraksha Yojana, Rajiv Gandhi Scheme for Empowerment of adolescent Girls, Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalaya, etc. nonetheless these schemes have not been able to assuage the condition of women belonging to the Gujjar and Bakkarwal community.

The following chart indicates the lack of awareness about government schemes for women.

Data from the World Bank suggests that at least 500 million females worldwide lack proper menstrual hygiene management facilities. Another interesting research on menstruation among Gujjar girls, including both nomadic and semi-nomadic discovered that 96% handled their menstruation in a “very poor” and harmful manner, including the usage of soiled fabric, inappropriate cleaning of old cloth, and insufficient drying mechanisms. The sample included 200 females between the ages of 13 and 15. The study found that the sample females lacked conceptual clarity regarding the menstrual cycle before they began menstruating, which resulted in several gynecological difficulties. Approximately 83% of the sample females learned about menstruation from their peers. The study further found the predominance of numerous sociocultural taboos associated with menstruation. Approximately 98% of the girls showed an aversion to bathing on a regular basis during their menstrual cycle.

Data from the World Bank suggests that at least 500 million females worldwide lack proper menstrual hygiene management facilities. Another interesting research on menstruation among Gujjar girls, including both nomadic and semi-nomadic discovered that 96% handled their menstruation in a “very poor” and harmful manner, including the usage of soiled fabric, inappropriate cleaning of old cloth, and insufficient drying mechanisms. The sample included 200 females between the ages of 13 and 15. The study found that the sample females lacked conceptual clarity regarding the menstrual cycle before they began menstruating, which resulted in several gynecological difficulties. Approximately 83% of the sample females learned about menstruation from their peers. The study further found the predominance of numerous sociocultural taboos associated with menstruation. Approximately 98% of the girls showed an aversion to bathing on a regular basis during their menstrual cycle.

The human development index of trans-human communities in India is terrible. On account of geographical remoteness and logistical challenges, the villages predominantly inhabited by the Gujjars and Bakarwals are neglected. Another barrier to accessing healthcare services is the scarcity of low-cost drugs allied with the burden of hefty transportation costs. Transportation costs frequently surpass diagnostic and medical costs. People generally rely on home remedies or natural herbs to treat ailments as a result of these inhibiting factors. Cattle farming is the mainstay of their subsistence economy. As a result, the expense of treatment is sometimes paid by selling the cattle. This leads to the loss of their source of income in order to facilitate the patient’s therapy.

Malnutrition and anemia have been found to be on the rise in adolescent indigenous females. Health activities aimed specifically at teenage females must be created, with health care delivered to their homes. A conference was held to discuss the tribal strategy for the years 2022-23, which showed intentions to offer healthcare facilities in Dhoks, tribal settlements, and transit accommodations along migratory routes. Plans were discussed for the early procurement of Mobile Medical Units and Ambulances for tribal areas with dedicated service contracts, dedicated Aarogya Mitras to assist tribal patients, Tribal ASHAs for extending healthcare services in Dhoks, and deputation of doctors and paramedic staff. It was said that the Tribal Affairs Department has given INR 14.50 Cr under the First Tribal Health Plan for the purchase of machinery and equipment for the migratory population.

Lt Governor Manoj Sinha spoke about the tribal health plan, tribal bhavans, and mobile medical care units in Jammu, Srinagar, and Rajouri in 2021. He also discussed the government’s plans for transhumance pastoralists’ long-term livelihood, which include 1500 mini-farms, milk communities, and marketing training for youngsters. Until now, these plans have remained on paper, and tribal activists claim that the Tribal Welfare Department has merely served as a nodal agency, receiving funds and distributing them to other departments without putting any checks and balances in place to ensure that the funds are used for the benefit of the tribal community.

Recommendations

On the front of fostering gender equality, improving the health of Gujjar women necessitates a significant and long-term commitment from the government. The Gujjar Community requires the development of dietary and health programmes. The health of the Gujjar and Bakarwal people is a difficult issue that requires a multifaceted strategy to effectively solve. While attempts have been made to address these communities’ difficulties, more needs to be done to increase access to healthcare, nutrition, and education. Because poverty, illiteracy, and a lack of basic utilities are prevalent among tribal people, the government, NGOs, and civil society should collaborate to reduce socioeconomic inequities and enhance the health indices of these marginalized populations.

Improving the health of Gujjar and Bakerwal women necessitates a strong and persistent commitment from governments and other stakeholders, as well as a favorable policy environment and well-targeted resources. Furthermore, health insurance plans should be prioritized, since their absence places a great load on the family’s budget. As a result, arranging an insurance policy for livestock losses should be considered.

Long-term increases in education and awareness opportunities will benefit Gujjar and Bakerwal women and their families health. Significant progress may also be made by enhancing and extending key health services for Gujjar and Bakerwal women, improving policies, and fostering more positive attitudes and behavior towards the health of Gujjar and Bakerwal women. Outreach programmes, mobile clinics, and community-based services can all be beneficial. Clustering services for women and children at the same location and time frequently improve beneficial interactions in health benefits and lowers Gujjar and Bakerwal women’s time and travel expenditures, as well as service delivery costs.

According to the Economic Survey of Jammu and Kashmir, Gujjars and Bakerwals make up more than 42% of the Scheduled Tribe population and live below the poverty line. As a result, the government should take a long-term strategy to boost the “tribal economy,” which is at the point of collapse owing to poverty and illiteracy. Transchumats and tribals are especially sensitive to climate change and global warming since they frequently live in steep and mountainous areas. They are frequently the first-hand victims of natural disasters. Disaster and first-aid training should be provided to them, particularly to kids, in order to preserve their health and lives.

References :

-

Health of the Gujjar and Bakarwal Communities in Jammu and Kashmir” by Dr. Parvaiz A. Koul and Dr. Pritam Singh

-

“Health and Nutrition Education Intervention Improves Infant Growth and Development among Nomadic Tribes in Jammu and Kashmir, India” by Dr. Nighat Yaseen Sofi and Dr. Shakila Maqbool

-

“Gujjar and Bakarwal of Jammu and Kashmir” by National Commission for Scheduled Tribes (NCST)

-

-

https://www.homesciencejournal.com/archives/2016/vol2issue3/PartF/2-3-52.pdf

-

https://en.gaonconnection.com/labour-pains-pregnant-gujjar-and-bakarwal-women-in-jk-struggle-to-access-medical-facilities/

-

-

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/kashmir-tribal-women-menstruation-gujjar-bakarwal/

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.