Traditionally, environmental issues have remained underrepresented in electoral politics worldwide. However, with climate change now a looming reality, environmental concerns are gaining traction both within nations and on global platforms to varying degrees. This article aims to explore the mainstreaming of environmental issues in electoral politics amid the increasing severity and scale of environmental disasters globally. Environmental issues encompass undesirable physical, chemical, or biological changes, challenges, and threats facing specific geographical regions and their ecosystems. These issues encompass a wide array of challenges, including the climate crisis, global warming, biodiversity loss, energy consumption, deforestation, desertification, plastic pollution, and general pollution. They are complex and interconnected. However, translating such environmental concerns into electoral agendas presents both a significant challenge and an opportunity. The issue of climate change has brought to the forefront the impacts of extreme weather events on social, economic, and political processes.

Global Overview

In 2023, the world experienced its hottest year in at least 173 years. Global average temperatures surpassed the 1.5°C warming threshold for the first time. Additionally, the severity of environmental disasters was underscored in the World Economic Forum (WEF) Global Risks Report 2024, which identifies extreme weather events and critical changes to Earth’s systems as the greatest concerns facing the world over the next decade. This underscores the significant threat environmental issues pose to biodiversity, making the mainstreaming of environmental concerns in electoral politics imperative. This trend began with environmental movements that brought attention to these issues within electoral politics.

Environmental movements have sustained a long struggle, initially emerging as mass movements that have subsequently evolved into political parties in various countries. Many of these movements have formed themselves into political parties, often referred to as green parties. It is noteworthy that green political parties and their environmental concerns originally centered on staunch opposition to nuclear power, warfare, and weapons industries. However, over time, their focus has broadened to encompass issues such as pollution, climate change, and industrial agriculture.

Most green parties adhere to four core principles: ecological sustainability, grassroots democracy, social justice, and nonviolence. They have increasingly asserted themselves within mainstream politics, particularly in Europe. Indeed, in Germany, green parties hold key positions within the government, including the foreign ministry.

Green parties have achieved significant levels of presence and authority in EU member states. Finland’s Green Party made history by becoming the first to be appointed to a national cabinet when its leader was named environment minister in 1995. In 2004, Greens entered government in Belgium, France, Italy, and Latvia. Indulis Emsis of Latvia notably became the first prime minister from a Green Party. By 2022, green parties held positions in national governments in Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Ireland, and Luxembourg, reflecting growing voter concerns about climate change and the diminishing appeal of mainstream parties.

Of particular interest is the emergence of the Green party as the fourth-largest group in the Federal Council. The 2019 Swiss Federal elections witnessed climate change as a major issue, and similarly, climate change featured prominently in the 2021 German federal elections. During the French presidential elections, President Macron pledged to prioritize environmental issues, positioning himself as an environmental president. In Brazil, presidential elections are heavily influenced by the imperative of preserving the Amazon.

Globally, green politics has not gained as much traction. Africa has seen various forms of environmental activism, with only a few electoral successes, such as the Green Belt Movement led by Kenyan Nobel Peace Prize laureate Wangari Maathai. Rwanda stands out as the sole African nation with green lawmakers in parliament. In Japan, Greens Japan was established in 2012 in response to the backlash against nuclear power following the Fukushima accident in 2011.

Greta Thunberg spearheaded the large youth-led and student strikes, known as Fridays for the Future, and the Green New Deal (GND) proposal, which has generated excitement globally, especially among young voters. Greta described climate change as an emergency that demands concerted action and global cooperation. In numerous countries, climate change issues have taken on a social justice perspective through indigenous climate movements and the Black Lives Matter campaign. Many businesses support climate action, with leading companies, including those in the oil and gas industry, committing to zero-emission goals since the 2015 Paris Agreement.

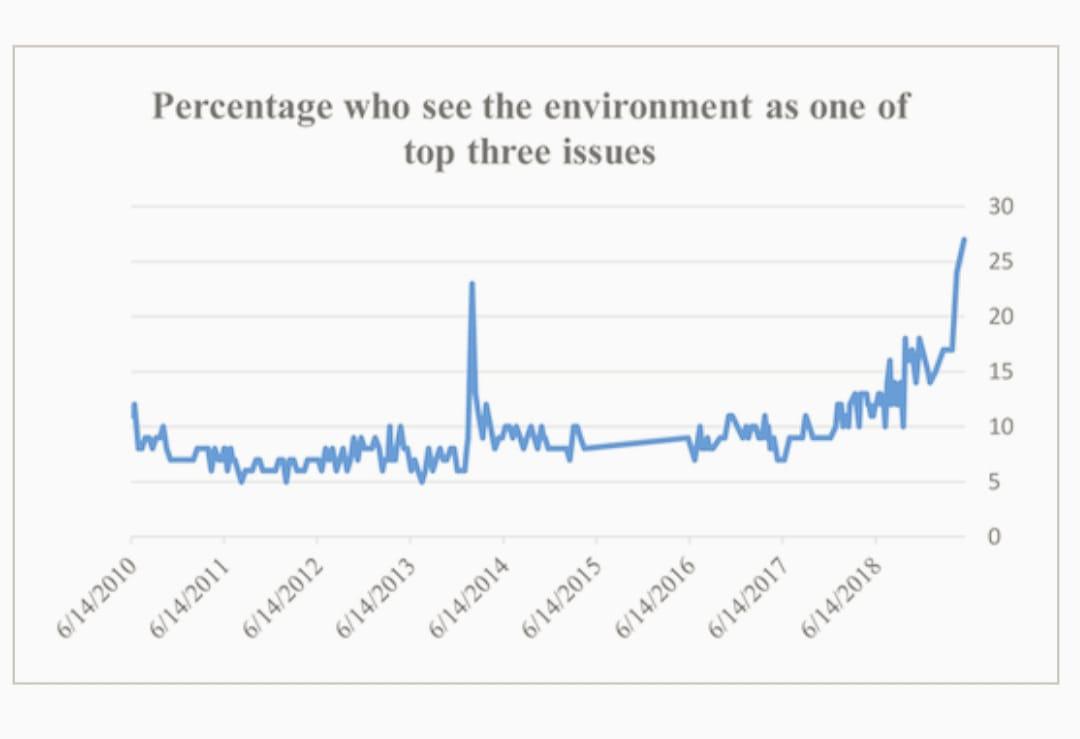

Key findings from a study conducted to evaluate the effect of flooding on British election results from 2010 to 2019 revealed that flooding was not widely covered in the UK press in the ten years preceding this period (Gavin et al., 2011). However, between 2010 and 2019, there was a notable increase in people’s general concern for the environment. According to YouGov tracker data, the percentage of respondents who considered the environment one of the nation’s top three issues consistently remained in the single digits at the beginning of the period. However, by 2019, this had changed, with between a quarter and a sixth of Britons expressing this opinion. The percentage who see the environment as one of the top three issues:

Indian Scenario

Environmental issues are increasing in both magnitude and frequency in India at an alarming pace. Urban cities such as Delhi and Bengaluru are grappling with severe problems of air pollution and water crisis, respectively. Meanwhile, Sikkim and Himachal Pradesh are still recovering from the unprecedented damages caused by devastating glacial lake outbursts and flash floods last year. Environmental issues are often relegated to secondary status despite their importance and receive little attention. One of the main reasons for this is the excessive focus of social and political movements on livelihood issues. Consequently, livelihood issues continue to hold centrality in national politics.

A recent report by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (YPCCC) and the Centre for Voting Opinion and Trends in Election Research (CVoter) in 2021-2022 indicates that 84% of Indians believe that climate change is real. The study further explains that most of them acknowledge that it originates from anthropogenic activities. Therefore, there is a need for a transition to renewable energy, energy efficiency, carbon pricing, reforestation, sustainable agriculture, education and awareness campaigns, and efforts to build climate resilience through local, national, and international cooperation.

In March 2019, research by Greenpeace International stated that 15 of the world’s 20 most polluted cities are located in India. It is estimated that one in eight Indian deaths is related to air pollution. According to a December 2018 Lancet Planetary Health study on the severity of pollution in India, supported by the Indian government, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Indian Council for Medical Research, 1.24 million Indian deaths were attributed to air pollution in 2017. Many documented air pollution-related deaths have been reported in the states of Maharashtra (108,038), Bihar (96,967), and Uttar Pradesh (260,028). Despite this alarming data, neither the political parties nor the electorate have ever raised the environment as a major concern during an election.

In recent years, India has experienced numerous instances of extreme weather, including irregular heatwaves, altered rainfall patterns, and other climate-related disasters that have caused widespread devastation and losses. According to the Delhi-based non-profit Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) and Down to Earth (DTE) Data Centre, there were extreme weather events on 314 out of 365 days in 2022. DTE claims that this indicates that on each of these days, at least one instance of extreme weather was recorded in some regions of the nation. Furthermore, another study conducted and published on July 7, 2021, in The Lancet Planetary Health journal revealed that there are 655,400 deaths in India each year related to abnormally low temperatures, while 83,700 deaths are connected to abnormally high temperatures.

Understanding the stance of political parties on environmental issues is noteworthy. Prior to the 2019 General Election, the two major political parties, the Congress and the BJP, mentioned the climate catastrophe for the first time in their manifestos. According to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) manifesto, the Himalayan states will receive special financial support in the form of “Green Bonuses” to aid in forest preservation and protection. The party’s manifesto also highlights the achievements of the Clean India Mission, or Swachh Bharat Mission. “Environment and Climate Change” and “Climate Resilience and Disaster Management” are two topics covered in the Indian National Congress’s (INC) platform. It proposes the establishment of “an Environment Protection Authority (EPA) that is transparent, independent, and empowered to establish, monitor, and enforce environmental standards and regulations.” Examination of the manifestos of regional parties also reveals awareness of the climate crisis. Parties like the DMK, Trinamool Congress, and NCP have included environmental themes in their manifestos.

By their very nature, the environment and public health are social and political issues with deep connections. Environmental degradation affects social cohesiveness, human and animal health, as well as the political, economic, and cultural aspects of well-being. According to Yogendra Yadav, a political scientist, “Air pollution or climate change will not become a political issue by itself, no matter how acute the problem. It has to be made into an issue.” Hence, it needs to be elevated to a problem. Since environmental concerns continue to be overshadowed by populist issues during elections, there is an urgent need for policy enclaves and researchers to collaborate in addressing environmental challenges. Thus, this political disconnect needs to be addressed, and environmental issues need to be mainstreamed in electoral politics.

Way Forward

Professor Katharina Ó Cathaoir at the University of Copenhagen argues for the need for solidarity among citizens concerning the right to health if the state is to recognize it. She emphasizes that important human rights principles such as transparency, proportionality, and solidarity deserve to be highlighted in this regard. In line with this argument, even noted environmentalist Sunita Narain opines that although air pollution features on the political agenda for heavily polluted urban centers like Delhi, the inclusion of environmental concerns in party manifestos does not reflect effective action on a sizable scale. Therefore, cooperative efforts are warranted between the center and states in this direction. However, she also highlights the bottlenecks in the current fractured and polarized political atmosphere, which hinder the prospect for cooperation.

Responding to demands is equally important. It’s crucial to understand that competitive politics not only addresses needs but also demands. This requires clear awareness and articulation. Voters must be able to connect consequences to causes and express them publicly. It’s also important to recognize that the aggregation of demands needs to be purposefully directed. In politics, demand is necessary but not sufficient. Therefore, these demands need to mobilize disparate groups who support and sustain them. Mere aggregation of demands does not fulfill the conversion of demand into political or legislative enactment; it requires sustainable solidarity and collective actions. Despite all this, the role of media is essential. It plays a crucial role in strengthening democratic institutions, which is why it is considered the fourth pillar of democracy. However, its silence on environmental issues is reprehensible. It has the sheer magnitude to highlight environmental issues and bridge the political disconnect. Finally, regardless of which political party is in power, there is a need for strict adherence to environmental laws.

References

- https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/is-climate-change-an-election-issue-in-india/article67726742.ece

- https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/environment/environment-in-elections-natural-disasters-overlooked-in-himachal-pradesh-poll-campaigns-95856

- https://planet.outlookindia.com/news/environment-and-elections-why-the-twain-dont-meet-news-417284

- https://thewire.in/environment/the-advent-of-environmental-issues-in-indias-elections

- https://www.theweek.in/wire-updates/national/2024/03/17/del25-elections-non-issues-environment.html

- https://ejpr.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1475-6765.12522

- https://www.epw.in/journal/2019/9/commentary/%E2%80%98environment%E2%80%99-election-manifestos.html

- https://cires.colorado.edu/news/us-voters-climate-change-opinions-swing-elections

- https://journals.plos.org/climate/article?id=10.1371/journal.pclm.0000043

- https://www.newindianexpress.com/web-only/2023/Jan/17/can-green-politics-take-centrestage-in-india-2538699.html

- https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/how-green-party-success-reshaping-global-politics

- https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/environmental-degradation-never-an-election-issue-in-india/

- https://thewire.in/environment/assembly-polls-how-environmental-issues-figured-in-the-electoral-discourse-of-political-parties

- https://in.boell.org/en/2024/04/22/why-politics-india-do-not-rally-environmental-issues

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/political-disconnect-why-environmental-issues-not-winning-votes-in-india/articleshow/108563256.cms

- https://theprint.in/opinion/smog-of-democracy-why-air-pollution-is-not-a-political-issue/767341/

- https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/most-of-mps-skip-discussion-on-air-pollution-in-rajya-sabha-119112101573_1.html

- https://rwi.lu.se/blog/covid-19-ensuring-the-right-to-health/

- https://www.newindianexpress.com/lifestyle/health/2021/Jul/09/over-7-lakh-deaths-in-india-per-year-linked-to-climate-change-lancet-study-2327688.html

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.