By Javaid Trali

Over the last several months, I revisited a range of books and literature on the recent political history of Kashmir, and I also had the privilege of engaging in important conversations with people of intellectual honesty. What continues to linger with me is the sense that we have often been too quick to reject individuals, or conversely, too late to recognise their transformative contributions.

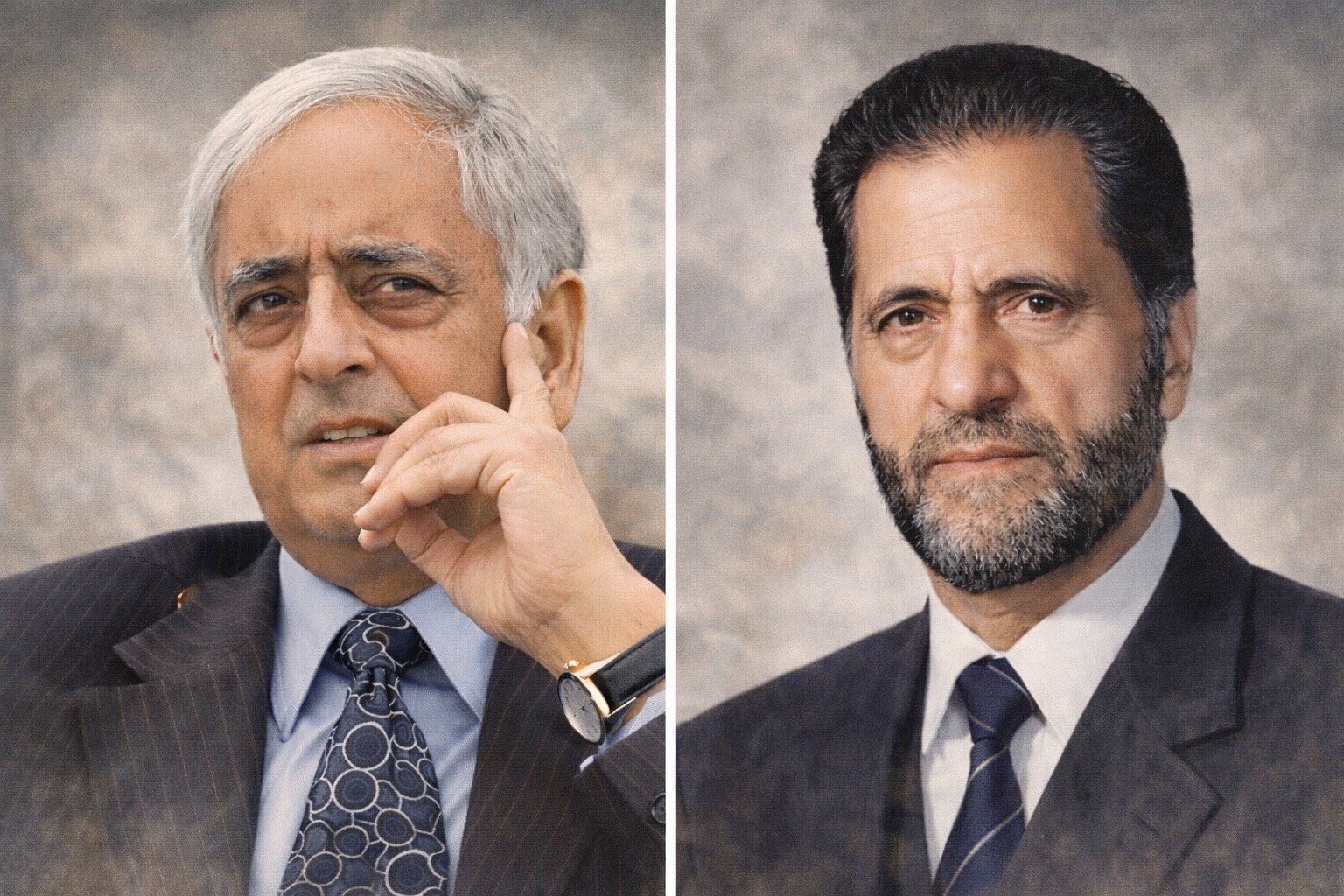

In the haze and maze of Kashmir’s political landscape, I have come to realise that public memory is often too short to recall those who acted in truly phenomenal ways. In my view, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed and Abdul Gani Lone are among such individuals.

This writing is neither an attempt to eulogise them nor to portray them as something they were not. Rather, I aim to offer a brief reminder of who they were, viewed through an academic lens, for the sake of record and reference. More importantly, it seeks to encourage healthy debate and critical evaluation of those who have shaped, positively or negatively, the public political behaviour of Kashmir and Kashmiris.

Mufti and Lone were very different men, shaped by different instincts and choices, yet bound by a seriousness of purpose that now feels increasingly rare. One worked almost entirely within electoral politics, the other left it for a period and swam with the tide of the times. Both, however, treated the conflict not as a slogan or a career opportunity, but as a political problem that demanded engagement and carried real risk.

Mufti Mohammad Sayeed never quite fit into the mould of a conventional politician. He came of age politically in post-1950s Jammu and Kashmir, beginning his career under G. M. Sadiq in the Democratic National Conference, which later merged with the Congress. Over time, Mufti held positions that few Kashmiri politicians ever have: Union Home Minister during the volatile period of 1989–90, and Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir in two difficult phases, from 2002 to 2005 and again between 2015 and 2016. These experiences shaped his belief that politics in Kashmir could not survive on confrontation alone, not with a mindset of conquerism but reconciliation.

At the heart of Mufti’s approach was a simple but costly idea: that force, by itself, could not resolve the issues. As Home Minister, at the onset of militancy, he pushed for political outreach and confidence-building measures. The release of detained militants during this period was controversial and widely criticised, but it reflected his conviction that reconciliation had to be attempted, even when it carried political risk. Years later, as Chief Minister after the 2002 Assembly elections, this thinking took institutional form in the “healing touch” policy. It was an imperfect effort, but its intent was clear: to restore dignity, political agency, and a sense of normalcy to a society battered by years of violence.

What Mufti underestimated was how fragile such a politics would be without sustained support. The People’s Democratic Party (PDP), which he founded in 1999, did alter Kashmir’s political landscape and broke the National Conference’s monopoly over regional politics. Yet the PDP never secured the kind of decisive mandate Mufti believed was necessary to carry forward deeper political or institutional reform.

Over time, the party’s weakening reflected more than electoral missteps. It exposed how difficult it had become to hold together a politics based on dialogue in an environment increasingly hostile to compromise.

During my association with the PDP, where I worked on the party’s communications, I saw this up close. My direct interactions with Mufti were limited, but his conduct in political settings was consistent. He discouraged the trademark political abuse, even in provocative situations. In one meeting, a party worker made a disparaging remark about Sheikh Abdullah. Mufti stopped him immediately. The point he made was not ideological; it was ethical. Politics, he insisted, loses credibility the moment it slips into personal denigration. That ethical commitment feels almost out of place in today’s political climate. Contemporary discourse in Kashmir has grown sharper, more reactive, and increasingly empty of long-term thinking. What is missing is not only vision, but restraint.

The most contentious moment of Mufti’s career remains the 2015 PDP–BJP coalition, forged after the fractured mandate of the 2014 Assembly elections. The criticism it drew was intense and, in many ways, justified. The decision rested on the belief that engagement with power at the Centre might stabilise the situation and create space for governance-led normalisation. In retrospect, that belief appears overly optimistic. The line between political pragmatism and misjudgement blurred, and the consequences were severe. The alliance damaged the PDP’s credibility and accelerated its political decline.

Yet it would be dishonest to reduce Mufti’s career to that episode alone. His earlier attempts to soften the security response, expand the meaning of governance, and make the state appear less distant to ordinary people still matter. Even where these efforts fell short, they shaped how Kashmiris began to talk about politics, accountability, and the limits of coercion.

Abdul Gani Lone represented a different political possibility altogether, one that Kashmir was never fully allowed to develop. He began his career in Congress and entered the Legislative Assembly in 1967. In 1978, he broke away to form the People’s Conference (PC), positioning himself against entrenched political arrangements.

As militancy escalated in the late 1980s and 1990s, his politics gradually moved outside formal institutions. Lone’s decision to align with the Hurriyat Conference was not a dramatic ideological leap, but a response to circumstances that left little room for conventional politics. As violence intensified and his workers were targeted, he chose to remain in Kashmir rather than withdraw from public life. That choice carried consequences. It tied him more closely to his constituency in Kupwara, but it also placed him in sustained danger. His assassination in May 2002 was not incidental. It was the outcome of a prolonged refusal to submit, either to militant diktats or to political irrelevance. He was rebellious, non-conformist and dangerously brave. His assassination mirrors all those unconventional leaders in world politics who were unambiguously rebellious and challenged everything that came in their way.

Outside Kashmir, Lone was taken seriously by sections of the international diplomatic community. His interactions, particularly with Americans, were marked by reason and clarity. He avoided theatrical language and instead articulated difficult, sometimes unpopular positions aimed at political resolution. At home, his credibility rested on consistency, on being present, accessible, and unwilling to trade autonomy for safety.

Despite the obvious differences between them, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed and Abdul Gani Lone shared certain traits. Both came from modest backgrounds. Neither inherited political power. Both stepped away from Congress to translate their ideal politics into reality. And both were deeply rooted in Kashmiri society, even as they expressed that rootedness differently. Mufti invested in institutional engagement and reconciliation. Lone drew his politics from rural realities, social justice, and empowerment of the pheran-clad, gullible, repressed Kashmiri.

When militancy reshaped Kashmir’s politics, their paths diverged sharply. Mufti remained firmly within the country’s institutional framework, even becoming part of the government at the national level (something that wasn’t lucrative then ) at the Union level. Lone articulated his dissent more vociferously while remaining at the vanguard of public resentment of the 1990s. Yet, for all this distance, both retained a measure of political dignity and seriousness that is increasingly difficult to find these days.

Looking back, leaders like Mufti Mohammad Sayeed and Abdul Gani Lone belonged to a creed of politics that has largely disappeared. Their choices were flawed and open to critique. They misread moments, took risks that did not always pay off, and left behind unresolved questions. But they engaged politics as something substantive, not performative. Their absence has narrowed the political field and eroded the space for a credible middle ground.

At a time when political life in Kashmir has become cautious, compressed and tightly managed, that loss continues to shape the J&K’s unresolved political crisis. Mufti and Lone invested their lives in Kashmir, not only when it was fruitful, but in all situations, they were the only political alternatives, but also choices and options of resolving issues of and in Kashmir; both were ideologues who moved with a pace that only they could race. Their political life is an important reference for resolving the issues with affection; Kashmir can’t be learnt without learning from their good and bad.

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.