India is transforming and transitioning at a rapid pace in areas such as infrastructure, digitalisation, and the service sector. However, despite this remarkable scale of growth, job creation has not kept pace with the growing labour force. This mismatch has led to a significant increase in unemployment. Unemployment is broadly defined as the condition in which individuals who are capable and willing to work at the prevailing wage rate are unable to find suitable employment. In India, unemployment is measured through indicators such as the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR), and Worker Population Ratio (WPR), primarily by institutions like the National Statistical Office (NSO), the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) and Unemployment Rate (UR).

The unemployment rate refers to the percentage of the labour force that is unemployed, while the labour force implies all individuals who are either employed or actively seeking employment. WPR defines the proportion of those who are employed among the total population. The unemployment rate is a key indicator of the health of an economy, as it reflects the availability of jobs and the overall level of economic activity.

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the Institute for Human Development (IHD)’s India Employment Report 2024, the proportion of India’s working-age population (aged 15–59) increased from 61% in 2011 to 64% in 2021 and is projected to reach 65% in 2036. Furthermore, the CMIE estimated that in June 2025, the unemployment rate in India stood at 8.5%, with the highest levels recorded in urban centres such as Delhi, Haryana, and Rajasthan.

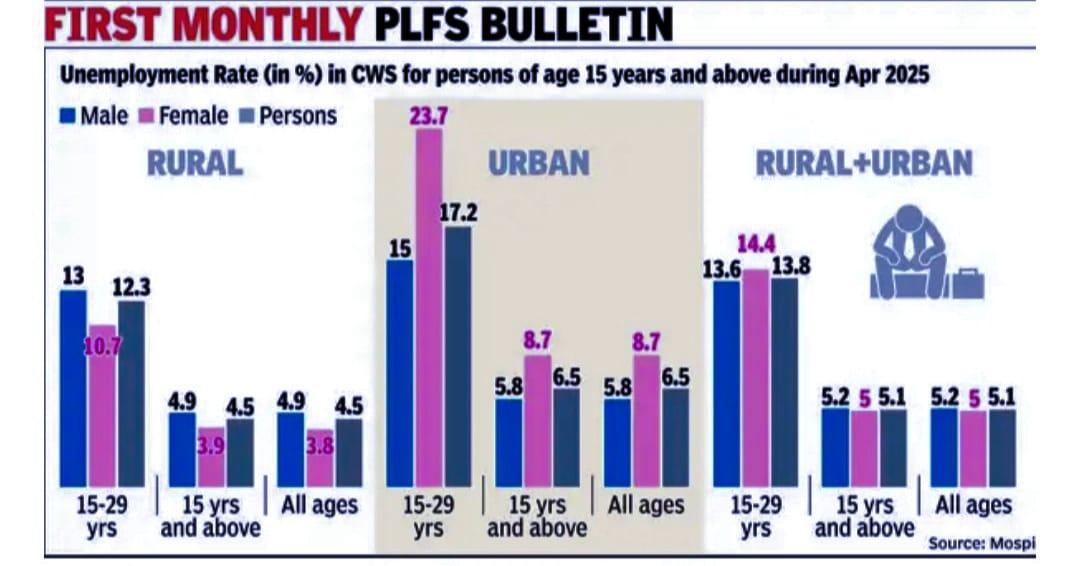

As per the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), India’s unemployment rate stood at 5.1% in April 2025 for individuals aged 15 years and above. Rural employment was recorded at 4.5% while urban joblessness was higher at 6.5%. The unemployment rates for men and women are 5.2% and 5%, respectively. Joblessness among individuals in the 15-29 age group was 13.8% nationwide. The rate of unemployment in urban and rural areas is 17.2% and 12.3% respectively. The study further indicated that joblessness among women in the age group of 15-29 was 14.4% across the country (rural+urban), while it was 23.7% in cities and 10.7% in villages. The Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) among people aged 15 years and above was 55.6% under the current weekly status (CWS), and LFPR among males aged 15 years and above in rural and urban areas stood at 79.0% and 75.3% respectively. LFPR implies the percentage of persons in the lobour force (working or seeking or available for work) in the population, while CWS provides an average picture of joblessness in a short period of seven days during the survey period.

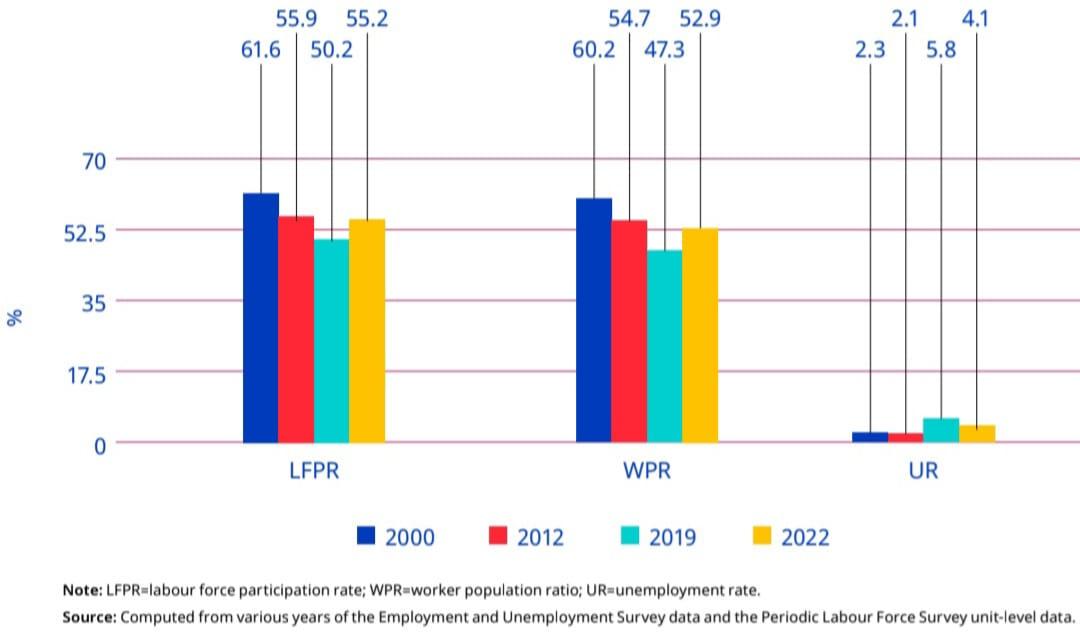

The LFPR in India for individuals aged 15 years and older was 55.2% in 2022, which was lower than the world average of 59.8%. It consistently declined over the past two decades, from 61.6% in 2000 to 50.2% in 2019, before increasing to 55.2% in 2022. The worker-population ratio also exhibited a similar trend, declining from 60.2% in 2000 to 47.3% in 2019 before increasing to 52.9% in 2022.

The LFPR in India for individuals aged 15 years and older was 55.2% in 2022, which was lower than the world average of 59.8%. It consistently declined over the past two decades, from 61.6% in 2000 to 50.2% in 2019, before increasing to 55.2% in 2022. The worker-population ratio also exhibited a similar trend, declining from 60.2% in 2000 to 47.3% in 2019 before increasing to 52.9% in 2022.

Labour Force Participation Rate, Worker Population Rate, & Unemployment Rate (UPSS) among persons aged 15plus (rural + urban combined), 2000, 2012, 2019 and 2022 (%)

Contextualising Jammu and Kashmir

Contextualising Jammu and Kashmir

According to the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and the Institute for Human Development (IHD)’s India Employment Report 2024, two out of every three unemployed individuals were young graduates. Regionally, all northern states (J&K, Punjab, Haryana, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh) and Southern states have unemployment rates higher than the national average, except Karnataka, as per the report. The unemployment rate in Jammu & Kashmir has reached alarming levels and continues to worsen each year.

Between 2001 and 2014, Jammu and Kashmir’s unemployment rate rose from 4.21% to around 5.4%, while its population grew from 10.14 million to 12.55 million. The labour force expanded by 15.15%, but the 2011 Census showed a low work participation rate of 34.5%, below the national average of 39.8%. Of the 4.32 million workers, 61.77% were main and 38.83% marginal workers. Women formed 26.09% of the workforce, with only 12.80% in main and 47.02% in marginal work. This indicated a rising trend of unemployment in J&K amid population and labour force growth, with low work participation, gender disparity, and a high share of women in marginal rather than main employment.

Even the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) asserted in its 2022 report that J&K’s unemployment rate stands at 25%, in stark contrast to the national average of 7.6%. According to this report, among all the Union Territories and states, Haryana has the highest unemployment rate, followed closely by J&K. Notably, due to the lack of a robust private sector in J&K, many people have little choice but to pursue government jobs, which is often cited as a major factor contributing to the region’s growing unemployment rate.

According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the unemployment rate in J&K stood at around 16-17% in 2018, nearly double the national average. As per the Economic Survey of J&K 2017-18, around 25% of youth aged 18–29 years were unemployed. The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) ranked J&K second in terms of educated youth joblessness, with Oxfam describing it as a “sea of unemployed youth.” The Economic Survey 2025-26 of J&K further revealed that nearly 46% of educated youth remain unemployed, indicating persistent structural gaps. While the number of industrial units registered has increased since 2020, with over 5000 new registrations as per UT government data by 2024, actual employment generation has remained limited due to delays in operationalisation. Promised national and foreign investments have yet to translate into substantial employment opportunities on the ground.

Sector-wise, approximately 70% of Jammu and Kashmir’s population depends on agriculture and its allied sectors, which have historically employed a large segment of the population. However, with rising literacy rates, most educated youth now prefer to pursue careers in the service sector rather than returning to agriculture. Due to the lack of industries, however, there are limited job opportunities in the service sector. According to the Directorate of Economics and Statistics, J&K 2017, the primary sector’s share has declined to 16.67%, while the industrial and service sectors’ shares have risen to 27.26% and 56.07%, respectively. Despite the secondary sector’s higher employment elasticity, it has not provided sufficient employment opportunities in the region, offering only limited jobs. Although agriculture remains the backbone of J&K’s economy, the sector has suffered from backwardness, stagnation, and a lack of mechanisation and technological advancement. Additionally, the secondary sector in Jammu and Kashmir has stagnated in terms of development, failing to create adequate job opportunities for the unemployed youth.

According to the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI), J&K’s unemployment rate decreased steadily from 6.7% in 2019–20 to 4.4% in 2022–23, then rose to 6.1% in 2023–24.

| Year | Unemployment Rate in % |

| 2023-24 | 6.1% |

| 2022-23 | 4.4% |

| 2021-22 | 5.2% |

| 2020-21 | 5.9% |

| 2019-20 | 6.7% |

Youth unemployment in J&K has touched 17.4% far above the national average of 10.2%. The overall unemployment is 6.7%, nearly double the national average of 3.5%, according to the Baseline Survey Report 2024-25 under Mission YUVA (Yuva Udyami Vikas Abhiyan), which cited the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) 2023-24. Women face even steeper barriers, with urban female unemployment recorded at 28.6%, underscoring the urgent need for inclusive economic interventions.

District-wise, Rajouri has the highest unemployment rate at 9.3%, followed by Anantnag at 8.7%. In contrast, Jammu and Srinagar report unemployment rates of 3.3% and 5.9% respectively, while Samba has the lowest unemployment rate at 3%. The report indicates structural shifts in the Union Territory’s economy, which has transitioned from an agrarian base to a service-dominated structure, with agriculture’s contribution declining from 28.06% in 2004-05 to 16.91% in 2022-23. Industrial growth remains stagnant, while the service sector has expanded to contribute 63.57% to the economy, highlighting the need for modernisation, industrial expansion and service-sector-driven entrepreneurship.

The Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation released a report titled “Periodic Labour Force Survey April-June 2021” which showed that the urban unemployment rate jumped to 12.6 % in April-June 2021 from 9.3% in the previous quarter. As per the report, J&K’s urban unemployment rate for the 15-29 age group has reached 46.3% from 44.1% in the previous quarter. As per the data, J&K’s unemployment in the educated category is the second-highest unemployment rate after Kerala, where the percentage stood at 47%. The report of the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) claims that Jammu and Kashmir’s unemployment rate for March 2022 was 25%, almost three times the national average for the month, 7.60%, and the second-highest after Haryana’s 26.7%. According to the CMIE, the data from April 2022 shows that the lack of jobs in Kashmir has resulted in a larger job crisis across the country.

Lack of employment can contribute to social, political or economic unrest, leading to potential conflict, individual or collective. It is also imperative to understand that J&K is a sensitive region geopolitically, which has witnessed a history of perpetual conflict. The anomie generated out of this can have a spillover impact on the youth, magnifying political or social unrest. A recent study by the World Economic Forum (June 2025) emphasizes on improving education, creating employment opportunities and entrepreneurship opportunities for youth in conflict zones through skills training, education, digital innovation, and inclusive policymaking, while also ensuring mental health support, cultural expression, and community engagement for long-term stability

Way Forward

Banks charging high interest rates discourage new entrepreneurs from creating gainful employment. High interest rates increase borrowing costs, making it difficult for new entrepreneurs to access capital. This discourages business creation, stifles innovation, and reduces job opportunities, leading to slower employment growth. Schemes offering lower interest rates should be introduced to promote entrepreneurship, boost startups, and generate more employment opportunities.

Women-led initiatives, especially in microfinance, can also bolster employment opportunities and play a crucial role in enhancing employment, especially in rural areas. Women are not only key beneficiaries of microfinance but also effective leaders and agents of change when given the right opportunities. Encouraging women’s leadership in microfinance institutions can lead to more inclusive lending practices, greater financial outreach, and the empowerment of other women entrepreneurs.

Microcredit, which promotes self-employment, must be integrated with social, educational, organisational support and leadership training programs, especially through group lending and social mobilisation. Bangladesh’s labour market participation has not only improved the gender gap but also created newer avenues of employment.

Despite various infrastructure and governance reforms in recent years, unemployment has not declined as expected. While development efforts have been made, job creation continues to lag, especially for educated youth seeking stable employment in both the public and private sectors. There is an urgent need to prioritise and promote youth employment, particularly in regions like Jammu & Kashmir, through vocational training, entrepreneurship, and inclusive economic opportunities to build resilience and reduce vulnerability.

The government should develop specific incentives that promote public-private partnerships (PPPs) to effectively address youth unemployment. These partnerships can leverage the advantages of both sectors: private companies provide innovation, efficiency, and market-driven training, while public institutions provide infrastructure and regulatory assistance.

The government can encourage businesses to fund apprenticeships, skill-development programs, and youth-focused job creation projects. Additionally, banks can create job opportunities by lowering borrowing rates for new business owners. Aspiring entrepreneurs can more easily obtain financing thanks to lower borrowing costs, which motivates them to start and grow their businesses. The banking industry can significantly contribute to entrepreneurship-driven economic growth and unemployment reduction by lowering financial obstacles, particularly in areas with few conventional employment options.

Conclusion

Tackling unemployment and promoting entrepreneurship in India, especially in regions grappling with economic stagnation like Jammu & Kashmir, demands a coordinated and multi-dimensional strategy. While infrastructure and governance reforms have laid some groundwork, the absence of targeted employment generation mechanisms continues to pose significant challenges. A singular focus on credit availability is insufficient unless accompanied by efforts to make financing accessible and affordable. Lowering borrowing costs, particularly for first-time and rural entrepreneurs, can catalyse business formation and drive local employment growth.

Equally important is the integration of women into the economic mainstream, not merely as recipients of microcredit but as active leaders and changemakers within financial ecosystems. Strengthening women’s leadership in microfinance institutions can foster inclusive lending practices, expand financial outreach, and inspire grassroots-level entrepreneurship, especially in rural and underserved areas.

Moreover, entrepreneurship cannot thrive in isolation. For it to contribute meaningfully to employment generation, it must be supported by robust social infrastructure, vocational education, organisational support, mentorship, and leadership training. Experiences from global examples like Bangladesh underscore the potential of combining microfinance with social mobilisation to bridge gender gaps and enhance labour market participation.

Finally, by encouraging structured public-private partnerships, incentivising skill-building initiatives, and realigning banking practices to support start-ups, the government can create a more enabling environment for job creation. An employment strategy built on these pillars will not only address immediate joblessness but also strengthen the foundation for long-term, resilient economic development.

References

-

-

-

https://www.jkpi.org/unemployment-in-jk-rising-challenges-and-the-need-for-economic-transformation/

-

-

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/unemployment-rate-at-5-1-in-april-shows-1st-monthly-survey/articleshow/121196555.cms

-

https://www.jkpi.org/mapping-the-unemployment-in-jammu-and-kashmir/

-

-

https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2024-08/India%20Employment%20-%20web_8%20April.pdf

Leave a Reply

You must belogged in to post a comment.